Georgia O’Keeffe and the Angel of Death

1. Where You Are Now

Georgia O’Keeffe was not the famous one, not the painter. Georgia O’Keeffe was a thirty-year-old corporate lawyer on a ski holiday with her boyfriend, Roman. They were in Megève, in the French Alps, where Roman had learned to ski as a child and where he’d taught Georgia to ski as an adult, six years ago. Before that, she had never heard of Megève.

It was two o’clock and bright enough for sunscreen. The mountains were stark against the blue sky: Le Jaillet, Le Christomet, La Cry, L’Alpette. Jagged peaks with names that crumbled in Georgia’s mouth. She and Roman joined the queue for the chairlift to Côte 2000: two days left of their vacation, and Roman was keen to tick off every black run in the resort, like he did every year. Black meant très difficile, followed by red (difficile), blue (intermédiaire) and green (facile).

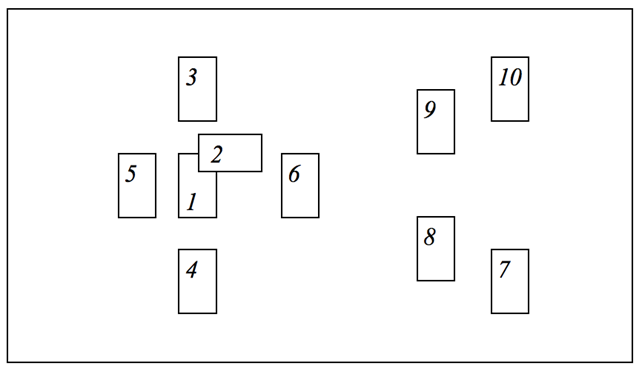

“Let’s be careful today,” said Georgia. She was the sensible one in their relationship—two years older than Roman, not that she liked to remind him of that. She also had a secret belief in the Occult, which she saw as compatible with her good sense. Her favourite tarot spread was the Celtic Cross. She’d been doing her daily readings locked in the bathroom of their Airbnb, and that morning, she’d drawn Death first, in the Where You Are Now position. Death wasn’t necessarily a bad card, but it still seemed like a good day to be cautious.

Roman turned a dial on his sports watch. “Hit ninety-two on that last run,” he said. “We can crack a hundred, though.”

By we, Roman meant I. Georgia did not ski at ninety-two kilometres per hour.

“I don’t know,” she said. She wished that Roman would slow down. Every time he rounded a bend and vanished, she started to worry. What if she fell and no one noticed? She’d fallen the first time he’d taken her skiing: she’d spun and tumbled, and her ski had snapped off. She’d had to hike back up the piste to get it, which had only been fine because she hadn’t been hurt.

Georgia had never told Roman about that fall, or any of the others. She hadn’t wanted him to think she couldn’t keep up. His beauty had silenced her in their first years together. He’d been so tall, so bright with his blond hair and expensive sunglasses. She still loved him now, of course, but for different reasons. She admired his confidence, the way he moved through the world. She only felt confident in bed—fully clothed, she lost her nerve.

“Maybe we should stick to red runs today,” she said and winced. Her voice sounded small and compressed, like ice cubes.

“You’re a good skier now, babe,” said Roman. His attention was on his watch.

Georgia sighed. She hoped that they were on the same page—the forever page—but she couldn’t be sure. Roman’s dad was an arms dealer and his mother was dead, so he’d grown up learning not to talk about his feelings. Georgia had grown up in Peckham, listening to her parents talk about the importance of sex and original thinking. They were both state-school art teachers who described themselves as activist artists. Other people called them free spirits, not seeing that they raised their daughter in a mesh made of rules: read this, hate this, don’t save for private property when private property shouldn’t exist. They hadn’t even given Georgia her own name. If she married Roman, she’d take his surname and lose O’Keeffe. As Georgia Kolomnikova, maybe she’d finally feel like herself.

2. The Challenge You Will Face

“Twenty-five-knot winds today,” said Roman, keying something into his watch. It was a Christmas gift from his dad, who expressed his affection through things, not words. He’d bought Roman a flat the year he’d graduated from uni. Mortgage payments are cheaper than rent, Roman had told Georgia, as if she were choosing not to buy property too. She’d had to withdraw from her ISA to cover her new ski outfit, but it was worth it—head-to-toe white with a faux-fur hood from Moncler. She almost fit in here. Every ski season she got a little bit closer.

Over the chairlift turnstiles, a dozen black birds rose and fell in the sunny air. One after another, they dove into the wind and were swept back to where they’d started from. They had orange beaks and orange feet. They weren’t going anywhere, but they kept diving and wheeling and swooping, like they were playing.

Georgia watched them for a while. She liked birds, not because they were pretty and could fly, but because wherever she went, she could count on them to be there. Little birds, loud birds, rare birds, city birds, birds of prey. Getting on with their bird lives in their parallel bird universe. In the tarot, birds represented freedom. Georgia had looked that up on the internet.

By the time she turned back to Roman, he was way ahead of her in the queue for the chairlift. He waved at her over the heads of a class of kids in Edmond de Rothschild team bibs. The ski teacher shunted them forward, and the kids shunted Roman forward, towards the lift. He shrugged at Georgia as he slipped through the gates.

In front of her, three little girls were speaking English in clipped accents. Only one of them was talking, really—a girl with brown eyes, chapped lips, and a pink helmet. Whenever silence fell, she filled it. “What’s your least favourite subject at school? Mine is spelling tests. We do them every day except Wednesday, and they take hours to correct on the board.”

Georgia pushed through the turnstiles, trying not to step on the girl’s skis. She felt a rush of warmth towards her, maybe because she wanted children, or maybe because she reminded her of herself—except Georgia’s family holidays had been camping in Scotland or picketing outside Whitehall in the rain. Not skiing in the most expensive part of the French Alps.

The lift scooped up the girl and her friends, and suddenly Georgia was next in line. The ski teacher shuffled sideways to join her, unmistakeable in her red monitrice outfit. She and Georgia pushed themselves onto the tapis magique, the plastic mat that rolled skiers into position. Georgia navigated it carefully, pretending she’d been skiing all her life. She was still thinking about the little girl as the chairlift hit the backs of their knees and swooped them into the air.

3. Your Conscious Goal

“Ms. O’Keeffe?” said the ski teacher, who was sitting to Georgia’s left.

Georgia turned. She couldn’t see much of the teacher’s face through her mirrored goggles. Her hair coiled out of her helmet in a thick blonde plait. “Um, have we met?” she said.

“No, but I know you.” The teacher smiled. “We need some snow,” she continued, nodding at the patchy slopes beneath their feet.

From what Georgia could see, the teacher was beautiful. Georgia was beautiful too, and she felt a jolt of competitive kinship: I have better legs. She has better teeth. Being in Roman’s world had taught her to see women that way. She wondered if the teacher might be American because her teeth were so good, but her accent was hard to place.

“Who are you?” Georgia asked, and realised too late that that sounded rude.

She didn’t pause. “I’m the Angel of Death.”

Georgia opened her mouth and closed it again. The Angel of Death? She looked away, at the sun on the snow. Roman would say that this lady was a nut job. But what a coincidence, to draw the Death card in the morning and then meet her in the afternoon. In Georgia’s tarot deck, Death was an armoured figure on a white horse, carrying a flag with a flower on it. The teacher didn’t look like that at all—or maybe she did. She was wearing a helmet, too.

“Don’t stress, honey,” she said. “You’re not on my list for today.”

“Your what?”

“My list of deaths.”

Georgia threw the teacher a look. “That’s not funny.”

“No. It’s very sad.”

They were nearing the peak now, where the chairs swung around and back down the mountain. Georgia couldn’t figure out how she felt about the woman beside her, so she focused on what she could see around her instead. Blank slopes. Blue sky. Sharp trees, their branches furry with snow. Roman, waiting at the disembarkation point, reading the piste map he only checked when he thought she wasn’t looking. She used to think that was sweet. She’d thought lots of things about Roman were sweet before she understood him, but sweetness was overrated.

“Almost there,” said the ski teacher. She pushed the security bar upwards, and it rose to meet the top of the bench.

Georgia tried to summon her confidence and failed. “It’s too soon,” she said, her voice tight. There were metres of empty air beneath them.

“Girl,” said the teacher, “I told you that today’s not your day.”

Georgia pressed herself back in her seat and tried not to look down. She willed the lift not to stop, not to pause. She ran her fingers over her forehead, smoothing it—until finally, her skis met snow. She launched herself away from the lift, towards Roman and the slopes.

“Catch you on the flipside!” called the teacher from behind her.

I hope not, thought Georgia. She didn’t turn around.

4. Your Unknown Influence

The snow was slushy, sticky, which Georgia liked because it slowed her down. When the sun started to set, though, the light became confusing. Three or four times, she had to turn into snowplough position to steady herself, with the tips of her skis angled inwards. Again and again, she’d let out a big breath before diving down the slope, reminding herself that she liked difficult runs. You’re a good skier now, Roman had said. Sometimes the wind held her back, and sometimes it pushed her on in gusts of speed. She held tight to her ski poles and told herself that she was having fun.

At around five o’clock, the sun dipped behind the peak. Light refracted past the snow cannon in a rainbow halo. “Look, babe,” said Roman, and for a moment it felt like their early days, when he’d opened so many doors for her. Taken her to dinners. Costume balls.

But then Georgia remembered the ski teacher. You’re a nut job, she said to her in her head, practising for the next time something like that happened. Looking back from the late afternoon, she saw that she hadn’t reacted to her correctly. Roman would have dismissed her right away, shut down the conversation with a few well-placed words.

“What’s up, babe?” said Roman.

“Nothing, darling.”

The only way back to Megève village at dusk was the ski bus. Roman hated public transport, but there was no other choice. Georgia clambered on first and found them seats near the back. The other passengers were ruddy and glowing, poking each other with ski poles and apologising in different languages. Georgia looked out of the window as the bus trundled into the valley. They passed a tiny, perfect airfield with a tiny, perfect plane in it.

In front of Georgia and Roman sat a pair of older women in fur. One wore a mink-trimmed jacket, and the other wore a hat that looked like it could be raccoon. “Did you hear about the children?” she said to her friend in English.

“Such a tragedy!” said the mink.

“Four dead!” said the raccoon.

Georgia wondered what they were talking about. She glanced at Roman, who was busy trying to get his sports watch to sync with his phone.

“The ski teacher too?” said the mink.

The racoon shook her furry head. “They’re still looking for her body.”

Georgia’s mind turned and clinked into place. The ski teacher’s body. Her body—and now four children were dead. Georgia saw them wobbling, tripping over each other, careening into a tree. Two trees. She saw their limbs bent over the branches, their team bibs scattered across the slope. And the ski teacher standing by, smiling her white smile.

Georgia closed her eyes, but the image was still there. Stupid. There was no Angel of Death. The brown-eyed girl who didn’t like spelling tests was probably eating crêpes with her family right now. This accident had probably happened to a different group of students from a different ski school. Georgia ought to be feeling sorry for the teacher whose body hadn’t been found, who was lost and alone on Côte 2000.

The two women didn’t talk for the rest of the journey. The raccoon spent it cleaning her goggles. The mink scrolled through Instagram on her phone. Georgia didn’t understand how they could drop the subject like that. Four children dead and a ski teacher missing: that wasn’t normal—or maybe it was? Georgia had been with Roman for six years now, but this still wasn’t her world.

“I’m hungry,” he said.

When they got back to their Airbnb, he ordered the Rothschild Pizza from the pizzeria next door. It had caviar and blue cheese on it and cost thirty-two euros. Georgia made herself eat two slices even though she wasn’t hungry. Caviar’s your favourite, she reminded herself.

5. Your Past Influence

The next morning, Georgia woke before her alarm. The sunlight was muffled, softened, even after she opened the lace curtains. It was snowing.

She got back into bed and snuggled up to Roman. He stirred, waking. She pressed her chest against his warm back, and he made a sound in his throat like a woodland animal, a smallish one. More beaver than moose. She kissed his neck and reached over his body to touch him. “Good morning,” she said, taking his hand and guiding it under the covers. She’d taught him to touch her the way she liked, gently, steadily, following her instructions.

Georgia loved sex with Roman. There was a time when it was so good it made up for all the difficult parts of their relationship—his lack of empathy, his dad’s refusal to meet her, the way she couldn’t always afford the right outfits for his parties. In bed, Georgia was the one in charge. Roman liked that too, though he would never say it in so many words.

Afterwards, Georgia locked the door to the bathroom and laid out her tarot cards on the floor. She drew The Lovers as her fifth card, in the Past Influence position. It wasn’t as good a card as it pretended to be: it meant romance, but also manipulation and sacrifice. The lovers weren’t even touching in the picture on Georgia’s card; they were standing a foot apart, naked, looking sort of sad. There was a snake in the tree behind them. Above them, an angel blocked out the sun.

6. Your Approaching Influence

By the time Georgia and Roman made it to the télécabine, it was clear that the snow was getting heavier. Roman wanted to ski anyway. He said that fresh powder made it feel like the ground wasn’t there at all. He squeezed Georgia’s hand as they stepped into the télécabine capsule, and Georgia squeezed back through both of their gloves. She was afraid, but things with Roman felt good this morning, and she didn’t want to let him down. She ran her fingers over her forehead, smoothing out the fear. She wanted to put off Botox for as long as she could. She wanted to be the fun, sporty woman she pretended to be.

And then she saw her on the slope beneath them.

The ski teacher wasn’t wearing her red monitrice outfit today: she was in a black jacket and green racing leggings, with her blonde braid coiling out of her helmet. Georgia knew her by the way she moved, shifting gracefully from ski to ski. Slung over her back was a sheaf of piste posts: giant toothpicks used to mark the edges of runs. She pulled one out of its place and planted it farther out, nearer the trees.

But you went missing yesterday, thought Georgia, remembering the conversation she’d overheard on the bus. Clearly that accident had happened to another ski group—or this ski teacher wasn’t a ski teacher after all.

“That job looks alright,” said Roman.

“It’s not her real job.”

The woman looked up from her piste posts, though she couldn’t possibly have heard them from so far away. She was wearing mirrored goggles again. She raised an arm and waved, like an out-of-town cousin in the British Museum. Hellooooo!

Georgia turned away from her, towards Roman.

“Do you know her?” he asked.

Georgia couldn’t explain—he would never believe her—but for once, she knew someone that Roman didn’t, and that felt good. “I do.”

“Who is she?”

“The Angel of Death.”

Roman snorted. “Jokes.” He turned back to his phone, which he had finally managed to sync with his sports watch.

“It’s not jokes,” said Georgia. “It’s very sad.”

Roman was deep in his ski app now, caught up in contour lines. “What’s sad?”

“Never mind.”

7. Your Inner Resource or Talent

All morning, Roman skied fast, and Georgia struggled to keep up. The snow was slick from melting and refreezing, and it was hard to spot patches of ice through the falling flakes. Often Roman ventured beyond the edges of the pistes, and Georgia pictured the Angel of Death rearranging the posts. Roman had nothing to worry about, of course: he could ski any slope. But Georgia couldn’t always control when she stopped, and despite Roman’s insistence that she was a black piste skier, she didn’t feel like one. She’d fallen so many more times than he realised.

Georgia’s friends, all law-degree blondes, claimed that they wanted to be really known by their partners, really understood. Georgia hated that idea. If Roman ever saw who she was on the inside, his interest in her would melt away. But there was no danger of that. Georgia was good at slipping through places without being found out for who she was.

8. How Others See You

Three hours later, Georgia suggested that they stop for lunch.

“We could try that place beneath the peak,” said Roman, pointing with his ski pole. He’d mentioned the restaurant on Mont Joly six times in five days. It had truffle raclette.

“But we’d have to do a chairlift,” said Georgia, “and another run.” Her shins were sore from leaning into her ski boots.

Roman shrugged. “It’s only a red.”

Georgia glanced around. She didn’t like that the pistes were empty today. People must have decided to stay inside for good reason. On the other hand, she didn’t want Roman to think that she wasn’t up for things. He had once told her that he liked adventurous girls. What he didn’t say was that he was looking for someone less like her and more like himself—someone who had skied all her life, and who had gone to one of those private schools that make you feel like you own the world because you do. Georgia had tried to be adventurous. She’d tried to be anyone but her mum, who said that life was tiring if you lived it ethically. Georgia didn’t want to be tired, but somehow she was, and she couldn’t figure out when or where her tiredness had begun.

There was no queue for the Mont Joly chairlift. As Georgia and Roman rose above the slopes, the air around them thickened with snow. The seats ahead of them and behind them vanished into whiteness. It was as though she and Roman were suspended in a void, not coming from anywhere and not going anywhere either.

At the disembarkation point, Georgia pulled her hood over her helmet and wrapped her scarf around her mouth and chin. She pushed off her ski poles behind Roman, moving faster than she’d intended. It occurred to her that she didn’t want to be there at all. Then the slope got steeper, and Georgia shifted her focus to not falling over. She didn’t have time to be scared now.

The red run didn’t feel like a red run. The wind was strong and Georgia couldn’t see a thing through her goggles. She followed Roman as closely as she could, but with each turn, he got farther away. He was right: the powdery snow made it feel like the ground wasn’t there, like she was weightless, floating through space with nothing to hold onto. Like she didn’t exist.

“Wait!” she called. Roman didn’t hear her, or he did but didn’t stop. Georgia turned her skis into snowplough position and watched him disappear.

For a moment, nothing happened. Georgia just stood there, feeling her muscles stiffen in the cold. Her lips were dry. Her legs were sore. And suddenly she was crying in funny little sobs. Georgia never cried, but it felt good now, if only to hear the sound of her own sniffles in the midst of this whiteness and silence. Her sobs proved she was still here, even if Roman wasn’t with her. She was skiing in Megève, and she was having an awful time.

Georgia sank to a squat and slouched sideways, her ski poles trailing from her wrists. What if she lay down right here, right now, in the snow? She could see why people caught in avalanches gave up and stopped digging for air. It would be so much easier to go to sleep, to stop trying to be the woman Roman wanted, the woman she had once wanted to be.

9. Your Hopes and Fears

“Ms. O’Keeffe?”

Georgia opened her eyes. A figure was standing over her, purple against the white sky.

“Get up, silly billy,” said the Angel of Death. “You’re not on my list for today.”

Fear pooled in Georgia’s chest. She coughed. “I’m alive?”

The Angel smiled. “You fainted, that’s all. Girl, you know you have low blood pressure, and you still didn’t stop for lunch.”

True, thought Georgia. But Roman didn’t believe that low blood pressure was a real thing.

“He’s an asshole,” said the Angel. “Who cares what he thinks?”

Georgia pushed herself up onto her elbows. She didn’t remember lying down. How long had she been there? The light over the piste seemed brighter than before, and the air was less dense. Georgia could see a few feet around her now. Maybe she’d been here for hours and Roman was at the bottom of the run somewhere, raising the alarm with the ski police. Georgia didn’t know if there was such a thing as ski police, but it seemed as though there ought to be.

Before Georgia had finished the thought, she knew that she was wrong. Wherever he was, Roman wasn’t looking for her. But the Angel of Death was, and not in a bad way.

“You can hear what I’m thinking, can’t you?” said Georgia.

The Angel bit her lip. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I can’t help it.”

“That’s okay.”

“You’re right, though. I am here to help you, not to kill you.”

“Oh good.” Georgia was surprised to feel herself smile.

“Come on.” The Angel extended her hand. “I’ll get you to the bottom in one piece.”

Georgia hesitated: this was the Angel of Death. She tried to see through her mirrored goggles to her eyes, but couldn’t get past her own reflection, crumpled up in the snow.

“Duh,” said the Angel. “If you were meant to die today, you’d be dead already.”

Fair enough. Georgia took her hand and wobbled to her feet. The Angel was wearing thick ski gloves trimmed with white fur. Through them, her hands felt the same as a normal person’s hands. Georgia wondered whether they were actually skeleton hands like in horror movies, then pushed the thought away, hoping the Angel hadn’t heard it.

“Don’t stress,” said the Angel. “I get that all the time.”

They started down the slope, the Angel leading the way, carving the snow like it was nothing to be scared of. She’d changed outfits since the episode with the piste posts. Her ski suit was purple now, with DAMEUR PISTE stamped across the back. Georgia followed her across the piste and back again in wide shallow zig-zags. At each turn, the Angel looked over her shoulder to check that Georgia was alright.

Zig, zag, zig. Another turn, and two more, and the slope flattened out.

“Told you,” said the Angel. A chalet restaurant glowed through the mist.

Georgia exhaled, long and slow. She felt like she might cry again, with relief this time. She imagined tears pooling in her goggles until they seeped out and froze in stripes down her cheeks.

“Oh shh,” said the Angel. “You’re welcome. And before you ask, Roman is inside, and he’s pissed off. They’re out of truffle raclette.”

9. Your Hopes and Fears, Continued, Because There Are So Many of Them

The snow let up at sunset. Georgia and Roman walked back through the village, past Hermès, AAllard, Acqua di Parma, and the patisserie. They crossed the town square and turned onto the road that climbed to their Airbnb. Icicles and fairy lights dripped from chalet roofs. Then the buildings fell away, unveiling the valley.

“Look, babe,” said Roman. “A dameur piste.”

Georgia put down her skis and looked. It was hard to distinguish between the dark sky and the mountains, but she figured that the sky began where the stars did. “What’s a dameur piste?”

“You know, a snow groomer.”

One of the stars was moving. Not blinking like a plane, but moving steadily over shadowy folds of snow, smoothing the pistes. “They do that at night?”

“They’ll be doing extra today, after the accident.”

Georgia looked away. “Those poor children.” The pistes should be smoothed all night long to stop something like that from happening again. She pictured the little girl with the chapped lips and the pink helmet, and her heart stung.

“No, I’m talking about the couple on Mont Joly,” said Roman. “Skied off a cliff. Ouch.”

Georgia swallowed. Mont Joly… She could see the disembarkation point now, and the red run descending into impenetrable whiteness. She could see the Angel in her purple ski suit, with DAMEUR PISTE on the back. She had been so comforting, and yet—Georgia pictured two people falling and landing in a jumble on the rocks. One wore a pink ski suit and one wore blue, like on the male and female WC signs in the town square. Georgia imagined the pink skier bleeding all over herself, the red clashing with her outfit, making a mess of the snow. She caught herself mid-thought and shuddered: blood clashing with her outfit? She sounded just like Roman’s friends’ girlfriends, or like one of those women in fur on the ski bus.

She turned back to the dameur piste, but she couldn’t find its light anymore.

“It’s gone,” said Roman. “Over the peak, onto the flipside.”

10. The Outcome

Another snowy day. Georgia locked herself in the bathroom and laid out her Celtic Cross. She drew the Six of Swords tenth, in the Outcome position, and looked up what it meant on her phone: she didn’t know the Minor Arcana by heart like her mum did. Change, transition, rites of passage, read one web page. Moving on, departure, distance, read another. The image on her card was of a canoe setting off on a journey. Its passengers were surrounded by six shining swords stuck into the body of the boat. Not a safe situation.

When she left the bathroom, Roman was already dressed. He’d tucked his fleece into his waterproof trousers and was eating a croissant. Flakes of buttery bread scattered across his ski jacket like snowflakes. “I’m not coming,” Georgia said.

“But it’s our last day.”

“I’m getting my period.” It wasn’t due for a week, but Roman didn’t keep track.

“Oh.” He brightened. “So I can do the pistes you vetoed on the Mont d’Arbois.”

Asshole, thought Georgia. “Enjoy,” she said and got back into bed. Roman hadn’t asked about her fictional period pains. He didn’t care how she felt. He didn’t care about her at all. And Georgia found to her surprise that that bothered her: it wasn’t enough to be admitted into Roman’s world. She wanted to be loved too.

“Ciao, babe,” he called from the corridor. He let the front door slam behind him.

Georgia counted to twenty and then put on a clean pair of socks. She swished around the apartment, noticing things she hadn’t noticed before, like the drawer full of Hitchcock cassettes and the VHS player above it. She chose a tape at random and switched channels until she got to the black-and-white film. The plot was ridiculous: a lady vanished on a train and another lady tried to find her while everyone else told her that the first lady didn’t exist. Of course, she turned out to be a spy delivering a message in the form of a song.

Georgia switched the VHS player to rewind. The apartment felt empty without Roman and she liked it. She pictured him skiing ahead of her on Mont Joly, into the whiteout. Then she pictured him tripping. Skiing off a cliff and landing broken in the snow. Ouch.

“Asshole,” said Georgia out loud.

The VHS player finished rewinding with a crunch. Georgia shook her head—what a horrible thought. Maybe she’d fallen out of love with Roman, or maybe she’d never been in love with him in the first place, but she didn’t want him to die. I don’t hate him that much, she thought and was taken aback: it had never occurred to her that she hated him.

She wiped the dust off the cassette with her sleeve and slipped it back into its case, feeling guilty. But it didn’t matter. Roman would never hurt himself skiing—unless someone pushed him or something tripped him or fell on top of him.

Georgia straightened up quickly, her mind clinking into place. The dameur piste, the snow groomer. And there had been avalanche warnings on the Mont d’Arbois.

She reached for her phone, trying to keep her hand steady. No messages from Roman. No answer when she called him. At ninety-two kilometres per hour, he couldn’t pick up, Georgia reassured herself. And then she remembered Roman’s watch. He had downloaded the ski app onto her phone on their first day in Megève, when his own phone wouldn’t sync.

She opened the app and flicked through to the Map Me tab. Black pistes crystallised beneath her thumbs. She zoomed in and scrolled and zoomed and scrolled again. Finally, there it was: the red dot that was Roman’s watch. It blinked, blinked, high up on the Mont d’Arbois, red and bright as a star, blinking and blinking on the spot.